The Missouri Compromise Explained

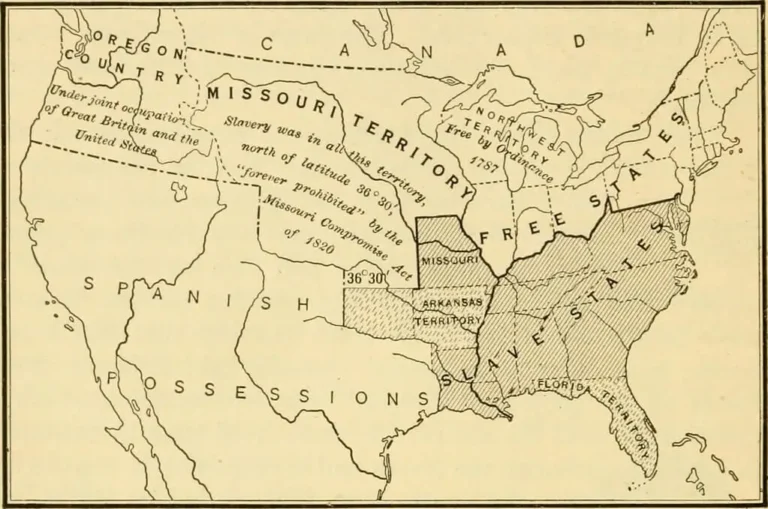

The Missouri Compromise, or Compromise of 1820, was an agreement reached in 1820 between the slaveholding and free states in the United States Congress to regulate slavery in the new territories in the West.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the contrasts between North and South were strong. The northern states were, on the whole, more populous than the southern states and their economy was based on trade and finance, while the southern economy was based mainly on large-scale agricultural production, especially cotton, which was very poorly mechanized and labor-intensive, employing 80 per cent of the local labor force. The northern states had gradually abolished slavery, which was rare in their territories, and the northern economic structure did not require the use of indentured labor. In the South, by contrast, the widespread use of slaves on the vast plantations was the backbone of the entire economy. Slavery was to become a major bone of contention between the North and the South, which later escalated into the War of Secession over the institutional form of the Union (Confederacy or Federation).

The Disagreement Between The North And The South

In 1803, with the ratification of the treaty between France and the United States, several territories became part of the union. In 1804, the colonization of Upper Louisiana began. From an agricultural point of view, the land on the lower Missouri River, from which the new state was to be formed, had no prospects as a major cotton producer. The only crop that was considered suitable for diversified agriculture and for slave labor was hemp. During the 1810s, especially after the end of the War of 1812 against the British, many southern planters migrated to the future Missouri Territory, bringing with them their goods and especially the slaves already working on the large southern plantations. In 1819, the Missouri Territory applied for admission to the Union. The territory had been settled mainly by whites from the southern states and in 1820 had six thousand black slaves (out of a population of about 66,000). The proposed constitution for the new state therefore protected slavery.

In February 1819, the proposal for annexation went before Congress. James Tallmadge, a congressman from New York, proposed that Missouri be admitted on the condition that it gradually abolish slavery. The Democratic-Republican congressman’s proposal caused a rift within the party, with many southern members opposed to the abolition of slavery. The southern states, with the exception of Georgia and South Carolina, had regarded slavery as a declining institution after the American Revolutionary War. This was evident in the shift to diversified agriculture in the Upper South; the gradual emancipation of slaves in New England and, more importantly, in the Middle Atlantic states. From 1790, with the introduction of the cotton gin, to 1815, with the huge increase in international demand for cotton, slave-based agriculture experienced an immense revival, spreading the institution westwards to the Mississippi River. Anti-slavery elements in the South faltered, as did their hopes for the imminent end of human slavery.

Continued Civil Conflict

Despite heated debate, the proposal was passed by the House of Representatives but stalled in the Senate. The dispute had a significant political underpinning. The problem for the slave-holding states was to prevent Congress from falling entirely under the control of the free states. The latter, which had overtaken the South in population, had already secured a majority in the House of Representatives, where each state sends several representatives in proportion to its population. Unlike the Senate, the distribution of seats was fixed, with each state having two seats. By 1819, Alabama had been annexed, allowing slavery and bringing the number of slaveholding states to eleven. With the same number of free states, the situation in the Senate was one of parity. Missouri would therefore tip the balance for or against slavery.

The debate lasted for over a year and showed the strong division between the northern and southern states. In 1820, Henry Clay, congressman and representative of the West, proposed to resolve the issue with what would go down in history as the ‘Missouri Compromise’. This compromise admitted Missouri to the Union as a state where slavery was permitted, and stipulated that slavery would not be permitted above the 36th parallel and 30′, the southern boundary of Missouri, in future annexations, making Missouri itself the exception to the newly created rule. To prevent the new state with slavery from upsetting the balance of power in the Senate, a new free state, Maine, was also admitted, separate from Massachusetts, of which it had previously been a part. The debate was so heated that many politicians of the time realized how explosive the issue of slavery could become for the Union.

Conclusion

Abraham Lincoln said that Clay had made a difference by preventing the country from plunging into civil war. To maintain the balance of power in Congress, the tendency to admit one free state and one slave state in succession continued until the Compromise of 1850. The next state to be admitted was indeed Arkansas (slave state) in 1836, quickly followed by Michigan (free state) in 1837. Two slave states (Texas and Florida) were admitted in 1845, opposed by the free states of Iowa and Wisconsin in 1846 and 1848. Four more free and non-slaveholding states were to be admitted before the outbreak of the Civil War. Constitutionally, the Missouri Compromise was important as an example of Congress’s exclusion of slavery from United States territory acquired since the Northwest Ordinance. However, the Compromise was deeply disappointing to black people in both the North and the South because it halted the South’s progress towards gradual emancipation on the southern border of Missouri and legitimized slavery as a Southern institution.

In 1854, the provisions of the Compromise were repealed, allowing slavery in the northern states and setting off a series of national tensions that were only the prelude to the War of Secession ten years later.